harvest season is here!

Dear Friends,

Since we sent our last newsletter, veraison has arrived, as you can see! The fruit is ripening nicely, and now we’re preparing for harvest season.

Over the next few weeks, Michael and our crew will be collecting grape samples representing the warmest and coolest spots in the vineyard, and everywhere in between. We’ll be tasting the fruit for ripeness, and also sending it to a lab to be tested for brix (sugar level) and pH (acidity).

We aren’t merely trying to gauge the ripeness of the flesh and skins of the fruit. We also check the stems and seeds. The stems should be slightly brown, and the seeds should be somewhat crunchy to bite down on.

We’ll be harvesting our Grenache for rosé production as soon as this week, since pink wines should be made from high-acid fruit. We’ll bring in the rest of our grapes, depending on variety, between mid-September and early October, when riper flavors have developed.

It’s essential to pick the grapes when they are cool, so we harvest during the lowest temperatures of the day, between midnight to 5am. This ensures that the fruit is firm and vibrant with acidity, and—most important—it doesn’t start fermenting spontaneously under the midday sun.

Although the majority of California vineyards—even the high-end ones—are machine-harvested these days, we always harvest by hand. Our vineyard rows are just too narrow and steep for machinery, and our artisanal winemaking style calls for careful sets of hands. Our pickers carefully gather the grape clusters in small bins, so the fruit isn’t crushed by its own weight, and inspect their pickings, tossing out any unripe or obviously damaged bunches.

When the fruit arrives at the winery, it goes onto a conveyor belt (see Michael, above). We pick through the clusters, tossing out rocks, leaves, and bad bunches before they are pulled into a destemmer. (Not all the clusters go to the destemmer, though. Read “Notes from the Cellar,” below, for more on this.)

In the wine industry, the work of processing and fermenting the fruit is referred to generally as crush, but at Mila Family Vineyards, we never actually “crush” our grapes. The destemming machine just cracks the skins a bit, before depositing the fruit onto another conveyor belt. This time, we look through the individual berries, tossing out any grapes that aren’t up to snuff.

Keep reading to learn more about “crush.” But first, a recipe…

from loretta’s sonoma table:

mom’s end-of-summer

italian cucumber salad

Every summer when I was growing up, my dad planted a vibrant vegetable garden, using 100-year-old seeds he had brought back from Italy.

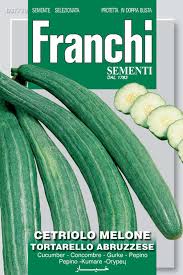

And so, as far as I knew, a “cucumber” was the tortenella.

It was long, its skin striped ultrapale jade and grass green, its rippled exterior rendering prettily shaped slices. I reveled in its satisfying crunch and divine, refreshing, almost-sweet flavor. (Little did I know that Italian cucumbers are closer to melons, genetically, than other cucumber varieties.)

The first time I bit into a flavorless standard supermarket cucumber, its skin coated with wax, I was disappointed to say the least. Even English and baby Persian cucumbers are, next to the colorful, flavorful tortenella, poor substitutes.

The tortenella is a rare indigenous variety from the Molise region of Italy, where my family is from, and thus the only place you’re likely to find it in the United States is in gardens like my dad’s and, now, mine, where Molisano dialect is still spoken. We keep up a friendly family rivalry every summer to see who can grow the tastier tortenellas.

However, I have seen a similar variety, the tortarello, from Abruzzo, in farmers’ markets as well as gourmet groceries in Sonoma. This is also called an Armenian cucumber, and comes in a bianco (very pale-green) variety, as well, but it lacks the colorful stripes and pure flavor of its cousin, the tortenella.

As for this salad recipe, I can never make it quite as well as my mom does, but I am proud to say that Michael served it to his bocce league, composed of Italian old-timers, and returned home to report that the gentlemen had become quite emotional upon tasting it. It brought them back, they said, to their own fathers’ vegetable gardens, and their own mothers’ kitchens.

For a print-friendly version of the following recipe, click here: RECIPE

ingredients

Salad:

4-5 tortenella (Molisan), tortarello (Abruzzan, or “Italian”), or Armenian cucumbers

3-4 garlic cloves, smashed and diced

2-3 banana peppers

4-5 Roma tomatoes, seeded and sliced thin

6-8 fresh basil leaves, julienned

3 tablespoons dried oregano

Dressing:

¾ cup of balsamic vinegar

1/3 cup of olive oil (I recommend McEvoy Ranch)

Salt, to taste

Pepper, to taste

½ cup of your favorite pesto recipe

directions

Slice cucumbers in half, lengthwise, and remove seeds. Slice each cucumber section crosswise into half-moons, approximately ¼ inch thich, discarding ends. Halve the banana peppers, remove seeds, and slice again, lengthwise, into strips, discarding stems. Repeat with Roma tomatoes, slicing into thin strips. Combine all salad ingredients in a large bowl.

Whisk together dressing ingredients in a separate bowl, then toss salad with dressing to serve. This salad marinates well and can be refrigerated for up to 3 days. (Drain any extra liquid, if needed, before re-serving.) Serves 4-6.

notes from the cellar:

a whole bunch of reasons

for whole-bunch winemaking

And now back to the action at the winery, at harvest time. We mentioned above that most, but not all, of the grape bunches go into the destemmer. That’s because we hold back about a third of our Grenache and Syrah clusters, with the stems intact, to ferment as they are.

Stems are a polarizing subject; every self-professed wine expert has a strong opinion about whether or not they should be included in fermentation tanks. As far as we are concerned, some of the greatest wines from the Rhône and Burgundy are made either partially or entirely with whole-cluster fermentation. That includes Château Rayas, an ultra-traditional estate in Châteauneuf-du-Pape which has long been an inspiration for us, so we had to give this technique a shot.

Over time, we have found that our vineyard seems to make the best Grenache and Syrah if we fill the bottom third of the fermentation tank with whole clusters, then layer loose berries over them. Over time, the weight of the berries on top crushes the clusters beneath, eventually creating a juicy, stem-studded soup like the one Loretta’s dad is checking out in this photo (from way back in the days when we fermented our grapes in bins).

It should be noted that whole-cluster fermentation works well for us because we don’t outright crush or press our red-wine grapes, since crushed skins and seeds can impart bitter, astringent tannins that we don’t want. (We get a lot less juice this way, but hey… no one ever said high-quality winemaking was cost-efficient.) But without their influence, we’re at risk of making a wine that could potentially be too one-dimensionally fruity. We find that the presence of some woody stems brings savory tannins, a pleasantly soft texture, spicy flavor, and a faintly floral aroma to our wines. In short, we believe that stem inclusion is the key to complexity in Grenache and Syrah.

learn our language

Whether or not you actually “crush” your grapes, crush is the insider’s term for the time period during and just after harvest when no one gets any sleep because there’s so much to do. And during crush, a lot of insider winemaking terms are thrown around.

As we’ve mentioned, we pick over our fruit three times before fermenting it, tossing out debris, bad bunches, and even bad berries. This process is called sorting. The initial field sort, shown in the photo above, happens out in the vineyard, where crew members toss out rotten or underripe bunches. Then there’s the second sort in the winery, sometimes called a hand sort (since we do the work by hand), as you can see Michael doing in this photo at the top of this page. Finally, there’s the berry sort, which might happen on a sorting table, which is a flat conveyor belt.

Harvest workers aren’t just looking for bad grapes when they sort. They’re also looking for MOG, or material other than grapes, which can be bugs, leaves, twigs, and so on. If the grapes have been destemmed, they also look for jacks during the berry sort; these are dried-up stems and vine debris that try to sneak into the fermenter.

And speaking of stems, you may have noticed that if you leave a bunch of grapes in a bowl on the kitchen counter for too long, the stems will dry out and shrivel. They have become woody, or totally lignified. At harvest time, we check the ripeness of the stems, since we do some whole-cluster fermentation. They should be starting to brown, but still supple. Some lignification is desirable, since green, underripe stems and seeds can be very astringent, but too much makes for dried-out, raisin-y flavors. Balance is key.

in the news

Rosé season is still going strong!

We were thrilled when Phil Masturzo selected our Rosé of Grenache as one of his favorites of the year in the Akron Beacon Journal.

We have a few bottles left in stock of the 2019 if you’d like to give it a try. We believe it’s our best vintage yet.

events

Ending in September (last chance!): Intimate Back Porch Parties!

Contact us at info@milafamilyvineyards.com to learn more.

Or: Book a private tasting at our Sonoma winery.

Contact Shelley at 440-915-5748 to arrange your appointment.

October 23: Gran Fondo Hincapie Celebrity Chef Dinner, Hotel Domestique, Travelers Rest, SC

November 5: T.J. Martell Foundation Best Cellars Dinner, Cleveland, OH